1, Néstor García

1, Néstor García

1*

1* https://doi.org/10.21068/c2021.v22n02a02

Diana López Diago

1, Néstor García

1, Néstor García

1*

1*

Recibido: 17 de diciembre 2020

Aprobado: 19 de abril 2021

Wild fruits have been an integral part of the diet of rural inhabitants in tropical America. In Colombia, information on the use of wild fruits appears scattered in the ethnobotanical literature and herbaria collections, limiting the design of conservation and use strategies. This review aims to synthesize information about the wild fruit species used in Colombia. We reviewed herbarium collections and literature references. We recorded 703 species in 76 families, among which Fabaceae (66 species), Arecaceae (58), and Passifloraceae (44) were the most diverse. The genera with more species were Inga (42), Passiflora (42), and Pouteria (21). Most species are widely distributed in tropical America, and only 45 (6.4 %) are endemic to Colombia. The regions with the largest number of species were the Amazon (388), Andes (144), and Pacific (111). Most of the recorded species, 613 (87.2 %), are exclusively wild, whereas 90 (12.8 %) are wild or cultivated. Wild edible fruits have a high potential for agriculture, novel products and nutritional improvement; however, it is vital to create strategies to revalorize their use.

Keywords. Biodiversity. Ethnobotany. Underutilized species. Wild foods.

Los frutos silvestres han sido una parte integral de la dieta de los habitantes rurales del trópico americano. En Colombia, la información acerca del uso de los frutos silvestres se encuentra dispersa en la literatura etnobotánica y en colecciones de herbario, limitando el diseño de estrategias de conservación y uso. Esta revisión tiene como propósito sintetizar información acerca de los frutos silvestres usados en Colombia. Se revisaron colecciones de herbario y referencias de literatura. Se registraron 703 especies en 76 familias, entre las cuales Fabaceae (66 especies), Arecaceae (58) y Passifloraceae (44) son las más diversas. Los géneros con más especies fueron Inga (42), Passiflora (42) y Pouteria (21). La mayoría de las especies tienen amplia distribución en América tropical, y solo 45 (6.4 %) son endémicas de Colombia. Las regiones con el mayor número de especies son Amazonia (388), Andes (144) y Pacífico (111). La mayoría de especies registradas, 613 (87.2 %), son exclusivamente silvestres, mientras que 90 (12.8 %) son silvestres o cultivadas. Los frutos silvestres tienen un alto potencial para la agricultura, para desarrollar productos novedosos y para mejoramiento nutricional; sin embargo, es necesario crear estrategias para revalorizar su uso.

Palabras clave. Alimentos silvestres. Biodiversidad. Etnobotánica. Especies subutilizadas.

Edible wild species grow with or without human action and need to overcome a process of human selection to be considered as domesticated crops (Heywood, 1999). The limits between both categories can be fuzzy, as more factors must be considered when classifying them. Wild edible plants and their products have been important throughout human history, not only for their nutritional benefits and impact on people’s diet, but also because they have shaped the ecological distribution and species richness across ecosystems (Levis et al., 2017). Despite their great influence, many of them have been underused due to knowledge loss, various factors, such as the arrival of new alternatives, or changes in the ecosystems and cultural diversity, caused a reduction in the use of native species (Byg & Balsev, 2004; Van Zonneveld et al. 2018).

In tropical America, fruits have been an essential component of diet and culture (Hernández & León, 1992). According to Patiño (2002), Europeans found in the Americas many communities that ate fruits as an integral part of their diet. Amerindian people from the Amazon domesticated at least 71 species of fruit trees (Clement,1999); for Andean cultures, fruits were related to social customs and were products of frequent exchange (Daza 2013, Martínez y Manrique 2014). However, while the native fruits were rooted in the diet of New World inhabitants, the European conquerors looked at them with suspicion (Patiño, 2002), introducing new fruit plants that quickly spread throughout the continent (Hernández & León, 1992). Many native species became underutilized due to the depopulation suffered by native American cultures and the transformation of their traditional knowledge after the European conquest (Clement,1999, van Zonneveld et al. 2018). Only in the 18th century, did American fruit trees begin to gain interest; by then, both native and introduced Old World plants had become part of home gardens (Patiño, 2002). Under this scenario, consumption of native fruits most probably decreased. Nevertheless, wild fruits are still an essential part of people´s alimentary traditions in tropical America (Patiño, 2002; Rivas et al., 2010; Álvarez et al., 2016).

Edible wild fruits contribute significantly to the diet of human communities (Baccheta et al., 2016). Wild fruits are an accessible source of food and income and are well-adapted to local climatic conditions (Bvenura & Sivakmar, 2017). Wild edible species and their varieties are valuable reservoirs of genetic diversity for crops (Bachheta et al., 2016). Genera like Annona, Solanum, Theobroma, Pouteria, Rubus, Passiflora, or Bactris, which include valuable commercial fruit trees, also have many wild species. Thus, these species can play an essential role in crop breeding, to increase the adaptability and resilience of commercial crops (Baccheta et al., 2016). This genetic potential of wild fruits can be related to incipient management and domestication (Baccheta et al., 2016). This could be, for example, the case of some palm species of Colombia, for which Bernal et al. (2011) identified management practices related to their edible use. It is also the case of species such as Vaccinium meridionale, currently in the process of cultivation and domestication in the Colombian Andes (Ligarreto, 2009). Thus, wild fruit trees may have the potential to increase agricultural diversity in many regions of Colombia.

Wild fruits are often richer in micronutrients and bioactive secondary metabolites than cultivated species, and they can benefit human health either by direct consumption or as processed products (Baccheta et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Bvenura & Sivakmar, 2017; Pinela et al., 2017). These favorable properties have been identified in numerous tropical fruit plants (Hernández & Barrera, 2010; Montúfar et al., 2010; Kang et al., 2012; Yamaguchi et al., 2015), increasing the interest in the development of nutritional products and dietary supplements (Oliveira et al., 2012; Neri-Numa et al., 2018). Any of these preparations could be considered as functional foods (Baccheta et al., 2016), which in addition to their nutritional properties, have positive physiological effects on consumers, potentially contributing to disease prevention and health improvement (Hilton, 2017). Along with the interest in biochemical research on wild fruit trees, the recovery of traditional knowledge about their management and preparation has contributed to their reintroduction as innovative foods for gastronomy and new cuisines (Baccheta et al., 2016). Therefore, wild fruit plants can diversify crop production and bring significant health and economic revenues to local communities, as they represent effective value chains (Kehlenbeck et al. 2013; Omotayo & Aremu 2020).

In Colombia, the diversity of wild fruits has been documented in several publications. Pérez-Arbeláez (1978), in his work "Plantas Útiles de Colombia" reported 50 species of fruit trees. Later, Romero-Castañeda (1991) compiled the most important synthesis about Colombia's wild fruits, reporting 167 species. However, as new revisions (Acero, 2005; Jiménez-Escobar & Estupiñán-González, 2011; Cárdenas et al., 2012; Mesa & Galeano, 2013; Ledezma-Rentería & Galeano, 2014; López et al., 2016b) and new field studies (Cárdenas & López, 2000; Cárdenas & Ramírez, 2004; López et al., 2006; Cruz et al., 2009; Estupiñan-González & Jiménez-Escobar, 2010; López et al., 2016a; Álvarez et al., 2016) have been accomplished, the number of reported species has increased. The use of many of these fruits are mostly local, so they have had little recognition for their contribution to Colombians' diet. In 2010, Rivas et al.(2010) conducted a study on indigenous food, finding 92 new species that had not been reported in the Colombian Food Composition Tables (TCAC), among which one third were fruits. This growing interest in native foods has allowed the resurgence of some wild fruits, which have gained popularity in specialized markets and in the country's research agendas. However, the information in Colombia about the use, nutritional and productive qualities is still scarce and disperse. Therefore, the present review aims to present a synthesis of the wild edible fruits of Colombia and to discuss their use prospects.

We conducted a literature search on Google Scholar and Science Direct databases. Search terms included "fruits", "native", "Colombia", "edible", "promissory" and "ethnobotany". There was no restriction regarding language or publication year. In total, 74 references among books, articles, technical-scientific reports, and dissertations were included. The search was complemented by a review of herbarium collections, including Colombian National Herbarium (COL), Antioquia University Herbarium (HUA), Javeriana University Herbarium (HPUJ), and Colombian Amazon Herbarium (COAH) (abbreviations follow Index Herbariorum). The list was built at the species level, including the following criteria: all species have at least one report as edible, are native to Colombia, and they are wild; all growth habits were considered. In some cases, where the species has wild and cultivated varieties, we decided to include or exclude it depending on our assessment of the use frequency of the wild variety; for example, we included Spondias mombin and Theobroma bicolor, but excluded Bactris gasipaes. Also, we included all species reported as edible fruits, regardless of whether it is the pericarp, aril, or accessory parts like hypanthium, perianth, or pedicel that are consumed, but excluded those in which only the seeds are consumed. Thus, we included Anacardium, Coccoloba, and Gaultheria species, of which the edible parts are the swollen pedicel or the fleshy calyx, but excluded, for example, Lecythis and Phytelephas, for which it is the seeds, either mature or immature, that are consumed.

The taxonomy followed the APG system and was based on World Flora Online Consortium and Catálogo de Plantas y Líquenes de Colombia. The spelling of scientific names was verified with the Taxonomic Name Resolution Service v4.0 (Boyle et al., 2013). Based on the literature or herbarium collections, we recoded the region of use for the species. The biogeographic regions were based on Catálogo de Plantas y Líquenes de Colombia and Hernández-Camacho et al. (1992). They included Amazon, Caribbean (including the Caribbean islands), Pacific, Orinoco (including Guayana and Serranía de La Macarena), Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Andes, Cauca Valley, and Magdalena Valley.

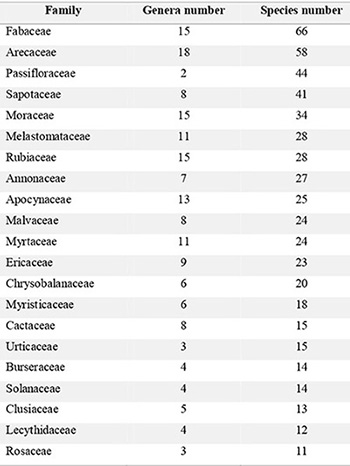

We found records of 703 plant species of wild edible fruits in Colombia distributed in 76 families (Appendix 1). The richest families were Fabaceae (66 species), Arecaceae (58), Passifloraceae (44), Sapotaceae (41), Moraceae (34), Rubiaceae and Melastomataceae (28 species each), Annonaceae (27), Apocynaceae (25), Malvaceae and Myrtaceae (24 species each), and Ericaceae (23) (Table 1). The most reported genera were Inga and Passiflora (42 species each), followed by Pouteria (21), Bactris (16), Annona (14), Pourouma (12), and Iryanthera and Solanum (10).

Table 1. Botanical families with more than ten wild fruit species recorded in Colombia.

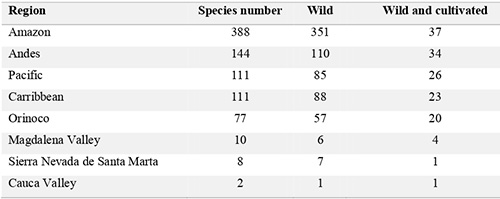

The regions with the highest number of species were Amazon (388), Andes (144), Pacific (111), Caribbean (111), and Orinoco (77) (Table 2). For 36 species, the region of use was not identified. We found that only 45 (6.4 %) of the recorded species are endemic. The region with the highest number of endemic species was the Andes, with 28 species, followed by the Pacific and Magdalena valley, with ten species each (Appendix 1).

Table 2. Number of wild edible fruits recorded in Colombia´s biogeographic regions, indicating the type of management (wild or wild and cultivated).

Eighteen species are used in almost all the regions of Colombia: Spondias mombin, Spondias purpurea, Bactris brongniartii, Oenocarpus bataua, Oenocarpus minor, Chrysobalanus icaco, Garcinia madruno, Dialium guianense, Hymenaea courbaril, Inga edulis, Bunchosia armeniaca, Pseudolmedia laevigata, Campomanesia lineatifolia, Eugenia victoriana, Passiflora foetida, Passiflora vitifolia, Genipa americana, and Pourouma bicolor (Appendix 1). In contrast, 541 species were reported as used only in one region, mostly in the Amazon (317), followed by the Andes (96), the Caribbean (52), and the Pacific (50).

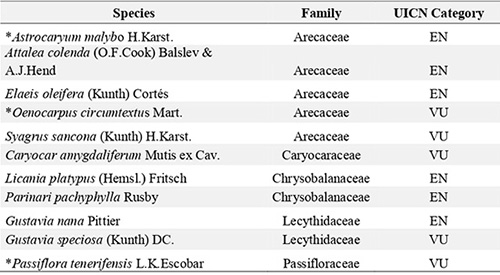

Most of the species recorded, 613 (87.2 %), are exclusively wild, whereas only 90 (12.8 %) species are both wild and cultivated. Amazon is the region with the highest number of wild species (351), followed by the Andes (110), Caribbean (89), and Pacific (85) (Table 2). Eleven species of wild fruits have been officially reported as threatened in Colombia (Calderón et al., 2002; 2005; Cárdenas & Salinas, 2007), six as endangered and five as vulnerable (Table 3).

Table 3. Wild edible fruits recorded in Colombia under threat of extinction according to the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. *Endemic species.

Wild edible fruit diversity. The number of wild fruits recorded here far exceeds the figures previously known for Colombia —50 species by Pérez-Arbeláez (1978) and 167 species by Romero-Castañeda (1991). This substantial raise is basically due to the increase of ethnobotanical studies during the last three decades (e.g., Patiño, 2002; Acero, 2005; López et al., 2006; Cruz et al., 2009; Jiménez-Escobar et al., 2011; Jiménez-Escobar & Estupiñán-González, 2011; Cárdenas et al., 2012; Mesa & Galeano, 2013; Ledezma-Rentería & Galeano, 2014; Álvarez et al., 2016; López et al. 2016a, b).

Although fruits have been the most frequent food category reported in literature for tropical America (Van den Eynden et al., 2003; Pulido et al., 2008; do Nascimento et al., 2013), their rich botanical diversity in Colombia is remarkable. The variety of Colombian ecosystems can explain this. Thus, Colombia appears to be a place of botanical convergence, rather than a center of origin of wild fruits. Passifloraceae and Ericaceae are the families with the highest numbers of endemic species, almost all them native to the Andes. The use of endemic species is sporadic, and except for Compsoneura cuatrecasasii (Patiño, 2002) and Hesperomeles goudotiana (Cardozo et al., 2009), there are no productivity or bromatological studies for them. Three of these endemic species are threatened; however, their condition is not related to overexploitation, but to natural habitat transformation (Calderón et al., 2002; 2005).

Palms appear to be one of the most diverse botanical group in our review. Their fleshy fruits are rich in vitamins, oils, and other nutrients (Montúfar et al., 2010; Kang et al., 2012; Yamaguchi et al., 2015), and they are a frequent component in the diet of rural communities across the territory. Mauritia flexuosa, Euterpe precatoria, and Oenocarpus bataua are widely appreciated in the Amazon and Orinoco (Acero, 2005; Mesa & Galeano, 2013), Euterpe oleracea and Oenocarpus bataua in the Pacific (Ledezma-Rentería & Galeano, 2014), and Bactris guineensis in the Caribbean (Galeano & Bernal, 2010). Even in the Andean region, edible fruits of palm species like Aiphanes horrida are usually consumed by rural people (Galeano & Bernal, 2010; López et al., 2016a). Some of these palm species have protocols for their harvest and management, as they have been promoted as non-timber forest products (Bernal & Galeano, 2013; López-Camacho & Murcia-Orjuela, 2020).

The legume and passion-flower families are also some of the most diverse groups, particularly the genera Inga and Passiflora. The consumption of Inga fruits has been frequently reported in ethnobotanical studies in tropical America (Lévi-Strauss, 1952; Cárdenas & López, 2000; Van den Eynden et al., 2003), and species of Passiflora are widely recognized for their edible fruits (Romero-Castañeda, 1991; Ocampo et al., 2007). At least 187 species of Passiflora are known in Colombia, and there are recent studies focused on their potential and conservation (Ocampo et al., 2007; Ocampo et al., 2010; Ocampo, 2013).

There is also a significant number of wild edible fruits of Sapotaceae, particularly from the genus Pouteria, for instance Pouteria arguacoensium, a fruit tree endemic to Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, traditionally used by the indigenous communities (Rivas et al., 2010). Among the Moraceae, although the genus Ficus was the most diverse, its fruits are only sporadically consumed, and have no commercial significance. Another diverse botanical group is Myrtaceae, for which there is a growing interest in using Myrciaria dubia (Hernández & Barrera, 2010) and Campomanesia lineatifolia (López et al., 2016a). Although Myrciaria dubia has been extensively used in Peru, reaching an international market, its potential is just beginning to be known in Colombia (Hernández & Barrera, 2010), and its fruits are now sold in some specialized markets. The two most diverse botanical groups of wild fruits used in Colombia's highlands are Ericaceae and Rosaceae. Vaccinium meridionale and Macleania rupestris are the most used species of Ericaceae. Whereas the former is widely commercialized and has been subject of several studies (Magnitskiy & Ligarreto, 2007; Ávila et al., 2009; Castrillón et al., 2008; Ligarreto, 2009; Medina et al., 2019; Díaz-Uribe et al., 2019), the latter is barely used (Acero & Bernal, 2003; López et al., 2016a). Andean rural people often consume wild Rubus species (Rosaceae), but they do not have commercial significance (López et al., 2016a). Apocynaceae, Melastomataceae, Rubiaceae, Malvaceae, and Annonaceae are other diverse families, that include species locally used and barely studied in Colombia.

Differences in the number of species among regions may be associated with ethnobotanical studies and biological and sociocultural aspects. According to Patiño (1989), until the 1990s, ethnobotanical studies in Colombia were focused on the lowlands, especially in the Amazon region. However, in the last two decades, there has been a growing interest in the ethnobotany of the Caribbean and Andean regions (Cruz et al., 2009; Jiménez-Escobar & Estupiñán-González, 2011; López et al., 2016a, b). In contrast, even today, the literature on the use of native flora of the Magdalena and Cauca valleys and the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is scarce, underlining the need to increase ethnobotanical research there. A recent study on food plants in the Magdalena Valley reported the use of only three wild fruits, which could be the result of sociocultural transformations, since virtually the entire indigenous population has disappeared from that region (Villa & García, 2017).

Recording the Amazon as the most diverse region for wild fruits is not unexpected, since they have been an essential component of the diet among the human groups living there (Hernández & León, 1992; Clement, 1999). Several ethnobotanical studies have reported the prevalence of the use of wild fruits in the Amazon (Cárdenas & López, 2000; Cárdenas & Ramírez, 2004; López et al., 2006). On the other hand, although the Andes are usually considered as the most transformed region in Colombia, it has more records of wild edible fruits than the Orinoco or the Pacific, which include extensive natural areas inhabited by human communities having have a deep relationship with the forest. The growing interest in the fruits of Ericaceae and Passifloraceae has contributed to the increase of the reports in this region (López, 2013; Abril, 2010). Likewise, in the Caribbean, recent studies have significantly contributed to the knowledge of useful species, including wild fruits (Cruz et al., 2009; Jiménez-Escobar & Estupiñán-González, 2011; López et al., 2016b).

Prospects of wild edible fruits. The most recognized species in literature are usually widely distributed in tropical America, so their use as food is well-known throughout the region. Due to their high potential for agriculture, for become novel products, and represent nutritional complement, most of them have been categorized as promising species, and have been gaining recent recognition in Colombia. Not surprisingly, some species like Euterpe precatoria, Euterpe oleracea, Mauritia flexuosa, Bactris guineensis, Myrciaria dubia, and Vaccinium meridionale are beginning to be traded in some of the largest cities of Colombia. However, some of these wild fruits have been marketed for decades in Brazil and Perú, whereas in Colombia, where studies on wild edible fruits are scarce, they are only a novelty in specialized markets. Some of the most studied wild fruits in Colombia include Amazonian species, especially Euterpe precatoria, Mauritia flexuosa, Oenocarpus bataua, Myrciaria dubia and Theobroma bicolor (Hernández et al., 1998; Hernández & Barrera, 2010; Montúfar et al., 2010; Kang et al., 2012; Castro-Rodríguez et al., 2015; Yamaguchi et al., 2015) and the Andean wild fruit Vaccinium meridionale (Ligarreto, 2009; Medina et al., 2019; Díaz-Uribe et al., 2019).

Since wild edible fruits have great potential for dealing with food and nutritional insecurity in rural communities (Bvenura & Sivakmar, 2017), it is important to characterize their biochemical and nutritional composition. A significant barrier for encouraging the safe use of our wild edible fruits is the lack of studies on nutritional properties. Rivas et al. (2010) pointed out the scarce attention paid in Colombia to studying the chemical composition of traditional foods. A worrisome situation is the frequent reports on wild foods that are toxic to humans (Guill et al., 1997; Spina et al., 2008; Abbet et al., 2014; Pinela et al., 2017). Caution is required with species such as Thevetia ahouai or Lantana camara reported as possibly toxic (Flores et al. 2001; Sharma et al. 2008). Although ethnobotanical reports validate the use of wild fruits, it is crucial to prioritize species with the most significant potential and encourage research on their bromatology. Wild fruits are also important sources of bioactive substances that can be used to develop pharmaceuticals and dietary supplements (Olivera et al., 2012; Bvenura & Sivakumar, 2017). Several bioactive substances have been identified in the best-known Colombian wild edible fruits; examples include the polyphenolic components with antioxidant properties of Euterpe precatoria and Euterpe oleracea (Yamaguchi et al., 2015), the heavy concentration of ascorbic acid in Myrciaria dubia (Yuyama et al., 2002) and vitamin A in Aiphanes horrida and Mauritia flexuosa (Balick & Gershoff, 1990; Pacheco, 2005) as well as the rich composition of aminoacids in Oenocarpus bataua (Balick & Gershoff, 1981). The search for new sources of bioactive substances should be an important line of research in Colombia, encouraging innovation in the food industry.

Another aspect of wild edible fruits is their potential to treat nutritional deficiencies. Anemia and micronutrient deficiencies (including vitamin A and zinc) are the most prevalent dietary problems in Colombia, particularly acute among rural people (Neufeld, 2012). However, consumption of wild edible fruits could solve some of these nutritional deficiencies. For example, fruits of Aiphanes horrida have been considered as an excellent source of Vitamin A (16.000 IU/100 gr) (Balick & Gershoff, 1990), and fruits of Hymenaea courbaril are rich in minerals such as iron, calcium, magnesium, zinc, silicon, phosphorus and potassium (Alzate et al., 2008). Wild edible fruits also provide other exceptional nutritional contents. “Milpeso milk” is a traditional beverage made from fruits of Oenocarpus bataua, which contains higher levels of proteins than soy milk (Balick & Gershoff, 1981). Also, the high content of Vitamin C of Myrciaria dubia and Malpighia glabra and the rich antioxidant contents of Bactris guineensis (Osorio et al., 2011), Vaccinium meridionale (Garzón et al., 2010), Mauritia flexuosa (Restrepo et al., 2016), and Euterpe spp. (Yamaguchi et al., 2015) are remarkable. Native fruits are also an alternative source of fiber, helping to decrease the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity, colon cancer, and other diverticular diseases (Olivera et al., 2012). Fruits of Byrsonima crassifolia, for example, were found to have anti-diabetic activity (Pérez-Gutiérrez et al., 2010).

On the other hand, the lack of detailed agronomical studies is a constraint for increasing native fruit production and their market availability (Olivera et al. 2012). We estimate that less than 20 % of Colombian wild fruits have studies on their agricultural production. This condition could be related to the acceptability and accessibility of wild foods. Consumer preference is another factor affecting the cultivation and resurgence of indigenous fruits and vegetables (Bvenura & Sivakumar (2017). Consumers often prefer exotic fruits and vegetables, especially those developed over the years, as they are well-known and easier to get (Bvenura & Sivakumar, 2017). Other aspects, such as low governmental interest, poor markets, lack of added value, and the inability to meet demand and standards, make the spread of wild foods problematic (Bacchetta et al., 2016). Since all these factors could be operating in Colombia, it is relevant to create strategies to re-assess fruits and other wild foods. Bacchetta et al. (2016) present some proposals that could be applied here. Firstly, we should prioritize species based on the information available and the prevalence of use. Here, it is essential to distinguish between those fruits of which consumption is just as a minor, incidental snack, from those with extensive use or those related to domesticated species, such as wild fruits of Annonaceae, Passifloraceae, or Myrtaceae. Then, we should assess available data and identify gaps through participatory ethnobotanical inventories. These activities might also involve collecting genetic material that remains as a priority to Colombian authorities due to the low representation of wild fruits in national germplasm banks. Based on the review of records from Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA) and Medina et al. (2009), we found that only about 31 (4.4 %) species are represented in national germplasm banks. Efforts for ex situ conservation of wild fruits could also facilitate conditions for studying their nutritional and agronomic requirements. However, conservation strategies should also include the protection of local knowledge and consumption, as many wild fruits are incorporated in people´s diets around the country (Rivas et al., 2010; Jimenez-Escobar & Estupiñán-González, 2011; Álvarez et al., 2016). Therefore, it is conceivable that wild fruits can play an essential role in different gastronomic traditions, so their commercial prospecting cannot be the only research focus.

Although our results account for a wide variety of wild fruits in Colombia, this does not necessarily reflect the reality of their current consumption. According to Rivas et al. (2010), native foods consumption has decreased in Colombia over time. Indigenous communities have replaced foods with others with higher social prestige but a lower nutritional value (Rivas et al., 2010). In other cases, consumption patterns have changed, due to recent socioeconomic transformations (Gómez et al., 2006; Álvarez et al., 2016). The drastic decline in consumption of wild foods has been attributed, among other factors, to forest degradation, agriculture, and urbanization (Bvenura & Sivakumar, 2017). However, the recovery of old habits is an essential strategy for promoting health and welfare (Rivas et al., 2010; Olivera et al., 2012). We expect that the growing trend to reevaluate native biodiversity and traditions will encourage research on our wild edible fruits.

We thank staff of the Colombian National Herbarium, Antioquia University Herbarium and Colombian Amazon Herbarium for providing access to their collections. This review article was supported by Programa Jóvenes Investigadores e Innovadores (Colciencias-Pontificia Universidad Javeriana).

Abbet, Ch., Mayor, R., Roguet, D., Spichiger, R., Hamburger, M. & Potterat, O. (2014). Ethnobotanical survey on wild alpine food plants in Lower and Central Valais (Switzerland). Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 15, 1624-634.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.022

Abril, D. (2010). Las ericáceas con frutos comestibles del Altiplano Cundiboyacense. (Thesis). Bogotá D. C.: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Biología. 41 pp.

Acero, L. E. (1979). Principales plantas útiles de la Amazonia colombiana. Bogotá D. C.: Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC). 263 pp.

Acero, L. E. (2005). Plantas útiles de la Cuenca del Orinoco. Bogotá: Zona Ediciones. 608 pp.

Álvarez, L. M., Gálvez, A. & Salazar, J. C. (2016). Etnobotánica del Darién Caribe colombiano: los frutos del bosque. Etnográfica, 20(1), 163-193.

https://doi.org/10.4000/etnografica.4244

Ariza, W., Huertas, C., Hernández, A., Gelvez, J., González, J. & López, L. (2010). Caracterización y usos tradicionales de Productos Forestales no Maderables (PFNM) en el corredor de conservación Guantiva-La Rusia-Iguaque. Colombia Forestal, 13(1), 117-140.

https://doi.org/10.14483/issn.2256-201X

Ávila, R., Orozco, O., Ligarreto, G., Magnitskiy, S. & Rodríguez, A. (2009). Influence of mycorrhizal fungi on the rooting of stem and stolon cuttings on the Colombian blueberry (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz). International Journal of Fruit Science, 9(4), 372-384.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15538360903378575

Baccheta, L., Visioli, F., Cappelli, G., Caruso, E., Martin, G., Nemeth, E., Bacchetta, G., Bedini, G., Wezel, A., van Asseldonk, T., van Raamsdonk, L., Mariani, F. & Eatwild Consortium. (2016). A manifesto for the valorization of wild edible plants. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 191, 180-187.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.05.061

Balick, M. J. & Gershoff, S. N. (1981). Nutritional evaluation of the Jessenia bataua palm: source of high-quality protein and oil from tropical America. Economic Botany, 35, 261-271.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02859117

Balick, M. J. & Gershoff, S. N. (1990). A nutritional study of Aiphanes caryotifolia (Kunth) Wendl. (Palmae) fruit: An exceptional source of vitamin A and high-quality protein from tropical America. Advances Economic Botany, 8, 35-40.

Bernal, R. & Galeano, G. (eds.). (2013). Cosechar sin destruir. Aprovechamiento sostenible de palmas colombianas. Bogotá D. C.: Facultad de Ciencias, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. 241 pp.

Bernal, R., Torres, C., García, N., Isaza, C., Navarro, J., Vallejo, M. I., Galeano, G. & Balslev, H. (2011). Palm management in South America. The Botanical Review, 77, 607-646.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-011-9088-6

Botero-Restrepo, H. (2005). Etnobotánica de la Cuenca Alta del Río Sinú. Córdoba, Colombia. Medellín: Fondo Para la Acción Ambiental, Fundación BIOZOO, Corporación Autónoma Regional de los valles de Sinú y del San Jorge. 91 pp.

Boyle, B., Hopkins, N., Lu, Z., Raygoza, J. A., Mozzherin, D., Rees, T., Matasci, N., Narro, M.L., Piel, W.H., Mckay, S.J., Lowry, S., Freeland, C., Peet, R. K. & Enquist, B. J. (2013). The taxonomic name resolution service: an online tool for automated standardization of plant names. BMC Bioinformatics, 14, 16.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-16

Bvenura, C. & Sivakmar, D. (2017). The role of wild fruits and vegetables in delivering a balanced and healthy diet. Food Research International, 99, 15-30.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2017.06.046

Byg, A., & Balslev, H. (2004). Factors affecting local knowledge of palms in Nangaritza valley in south-eastern Ecuador. Journal of Ethnobiology, 24(2), 255-278.

Caballero, R. (1995). La etnobotánica en las comunidades negras e indígenas del delta del río Patía. Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala. 248 pp.

Carbonó, E. (1987). Estudios etnobotánicos entre los Coguis de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. (Thesis). Bogotá, D.C.: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Biología. 155 pp.

Cárdenas, D. & López, R. (2000). Plantas útiles de la Amazonía Colombiana - Departamento del Amazonas - Perspectivas de los Productos Forestales No Maderables. Bogotá D. C.: Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas (SINCHI), Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. 113 pp.

Cárdenas, D. & Ramírez, J. (2004). Plantas útiles y su incorporación a los sistemas productivos del departamento del Guaviare (Amazonia Colombiana). Caldasia, 26(1), 95-110.

Cárdenas, D. & Salinas N. (2007). Libro Rojo de Plantas de Colombia. Volumen 4: especies maderables primera parte. Serie Libros Rojos de Especies Amenazadas de Colombia. Bogotá D. C.: Instituto de Investigaciones Científicas Sinchi - Ministerio de Ambiente, Vivienda y Desarrollo Territorial. 232 pp.

Cardozo, E.H., Córdoba, S.L., González, J.D., Guzmán, J.R., Lancheros, H.O., Mesa, L.I., Pacheco, R.A., Pérez, B.A., Ramos, F.A., Torres, M.A. & Zúñiga, P.T. (2009). Especies útiles en la región Andina de Colombia. Tomo II. Bogotá D. C.: Jardín Botánico de Bogotá. 285 pp.

Castro, F., Ocampo-Durán, A., Recio, L. P. & Sanabria, D. P. (2013). Palmas nativas de la Orinoquía: biodiversidad productiva. Serie Palmas Nativas No.1. Bogotá D. C.: Fundación Horizonte Verde. 91 pp.

Castro-Rodríguez, S.Y., Barrera-García, J. A., Carrillo-Bautista, M. P. & Hernández-Gómez, M. S. (2015). Asaí (Euterpe precatoria) - cadena de valor en el sur de la región amazónica. Bogotá D. C.: Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas (SINCHI). 142 pp.

Clement, C. R. (1999). 1492 and the loss of Amazonian crop genetic resources. I. The relation between domestication and human population decline. Economic Botany, 53, 188-202.

https://doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02866498

Córdoba, S., Guzmán, C., Pérez, J. R., Zúñiga, B. A., Upegui, P. T. & Pacheco, R. A. 2010. Propagación de Especies Nativas de la Región Andina. Bogotá D. C.: Jardín Botánico José Celestino Mutis. 235 pp.

Cruz, M. P., Estupiñán, A. C., Jiménez-Escobar, N. D., Sánchez, N., Galeano, G. & Linares, E. (2009). Etnobotánica de la región tropical del Cesar, Complejo Ciénaga de Zapatosa. In Rangel, O., (Ed.). Colombia, Diversidad Biótica VIII: media y baja montaña de la serranía de Perijá. Pp. 417-447. Bogotá D. C.: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Daza, B. Y. (2013). Historia del proceso de mestizaje alimentario entre España y Colombia. (Thesis). Barcelona: Universidad de Barcelona. 494 pp.

Díaz-Uribe, C., Vallejo, W., Camargo, G., Muñoz-Acevedo, A., Quiñones, C., Schott, E. & Zárate, X. (2019). Potential use of an anthocyanin-rich extract from berries of Vaccinium meridionale Swartz as sensitizer for TiO2 thin films – An experimental and theoretical study. Journal of Photochemistry & Photobiology A: Chemistry, 384, 112050.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.112050

do Nascimento, V. T., de Lucena, R. F. P., Maciel, M. I. S. & de Albuquerque, U. P. (2013). Knowledge and use of wild food plants in areas of dry seasonal forests in Brazil. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 52(4), 317-343.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2012.707434

Estupiñán-González, A. C. & Jiménez-Escobar, N. D. 2010. Uso de las plantas por grupos campesinos en la franja tropical del Parque Nacional Natural Paramillo (Córdoba, Colombia). Caldasia, 32(1), 21-38.

Galeano, G. & Bernal, R. (2010). Palmas de Colombia-Guía de Campo. Bogotá D. C.: Editorial Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Facultad de Ciencias-Universidad Nacional de Colombia. 688 pp.

Garzón, G. A., Narváez, C. E., Riedl, K. M. & Schwartz, S.J. (2010). Chemical composition, anthocyanins, non-anthocyanin phenolics and antioxidant activity of wild bilberry (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) from Colombia. Food Chemistry, 122(4), 980-986.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.03.017

Gómez, L., Arango, J. U., Siniguí, B., Domicó, M. & Bailarín, O. (2006). Estudio etnobotánico y nutricional de las principales especies vegetales de uso alimentario en territorios de las comunidades Embera de selva de Pavarandó y Chuscal-Tuguridó (Dabeiba Occidente de Antioquia). Gestión y Ambiente, 9(1), 49-64.

Guill, J. L., Rodríguez-García, I. & Torija, E. (1997). Nutritional and toxic factors in selected wild edible plants. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 51(2), 99-107.

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007988815888

Hernández-Camacho, J., Hurtado-Guerra, A., Ortiz-Quijano, R. & Walschburger, T. (1992). Unidades biogeográficas de Colombia. In Halffter, G. (Ed.). La diversidad biológica de Iberoamérica I: Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo. Pp. 105-152. México: Instituto de Ecología.

Hernández, M. S. & Barrera, J. A. (2010). Camu camu. Bogotá D. C.: Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas (SINCHI). 148 pp.

Heywood, V. H. (1999). Use and potential of wild plants in farm households. Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 113 pp.

Hilton, J. (2017). Growth patterns and emerging opportunities in nutraceutical and functional food categories: Market overview. In Bagchi, D. & Nair, S. (Eds.). Developing New Functional Food and Nutraceutical Products. Pp. 1-28. London: Elsevier.

Idárraga, A., Ortiz, R., Callejas, R. & Merello, M. C. (Eds.). (2011). Flora de Antioquia. Catálogo de las plantas vasculares. Vol. II. Programa Expedición Antioquia-2103. Series Biodiversidad y Recursos Naturales. Bogotá D. C.: Universidad de Antioquia, Missouri Botanical Garden y Oficina de Planeación Departamental de la Gobernación de Antioquia. Editorial D´Vinni. 939 pp.

Jiménez-Escobar, N. & Estupiñán-González, A. 2011. Useful trees of the Caribbean region of Colombia. Bioremediation, Biodiversity and Bioavailability, 5(1), 65-79.

Jiménez-Escobar, N., Albuquerque, U. & Rangel-Ch, O. (2011). Huertos Familiares en la bahía de Cispatá, Córdoba, Colombia. Bonplandia, 20(2), 309-328.

Kang, J., Thakali, K. M., Xie, Ch., Kondo, M., Tong, Y., Oub, B., Jensen, G., Medina, M. B., Schauss, A. G. & Wua, X. (2012). Bioactivities of açaí (Euterpe precatoria Mart.) fruit pulp, superior antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties to Euterpe oleracea Mart. Food Chemistry, 133(3), 671-677.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.01.048

La Rotta, C. (1983). Observaciones etnobotánicas sobre algunas especies utilizadas por la comunidad indigena andoque (Amazonas, Colombia). (Thesis). Bogotá D. C: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Biología. 117 pp.

La Rotta, C., Miraña, P., Miraña, M., Miraña, B., Miraña, M. & Yucuna, N. (1989). Especies utilizadas por la Comunidad Miraña. Estudio Etnobotánico. Bogotá D. C.: Fondo FEN Colombia. 381 pp.

Ledezma-Rentería, E. D. & Galeano, G. (2014). Usos de las palmas en las tierras bajas del Pacífico Colombiano. Caldasia, 36(1), 71-84.

https://doi.org/10.15446/caldasia.v36n1.43892

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1952). The use of wild plants in tropical South America. Economic Botany, 6(3), 252-270.

Levis, C., Costa, F., Bongers, F. & 150 more authors. (2017). Persistent effects of pre-Columbian plant domestication on Amazonian forest composition. Science, 355 (6328).

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal0157

Li, Y., Zhang, J. J., Xu, D. P., Zhou, T., Zhou, Y., Li, S. & Li, H. B. (2016). Bioactivities and health benefits of wild fruits. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(8), 2-27.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17081258

Medina, C. I, Lobo, M. & Martínez, B. (2009). Revisión del estado de conocimiento sobre la función productiva del lulo (Solanum quitoense Lam.) en Colombia. Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria, 10(2), 167-179.

Medina, C. I., Martínez, E. & López, C. A. (2019). Phenological scale for the mortiño or agraz (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) in the high Colombian Andean area. Revista Facultad Nacional de Agronomía Medellín, 72(3), 8897-8908.

https://doi.org/10.15446/rfnam.v72n3.74460

Mesa, L. & Galeano G. (2013). Usos de las palmas en la Amazonía Colombiana. Caldasia, 35(2), 351-369.

Montúfar, R., Laffargue, A., Pintaud, J. C., Hamon, S., Avallone, S. & Dussert, S. (2010). Oenocarpus bataua Mart. (Arecaceae): rediscovering a source of high oleic vegetable oil from Amazonia. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society, 87(2), 167-172.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-009-1490-4

Neri-Numa, I. A., Soriano Sancho, R. A., Pereira, A. P. A., Pastore, G. M. (2018). Small Brazilian wild fruits: Nutrients, bioactive compounds, health-promotion properties and commercial interest. Food Research International, 103, 345-360.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2017.10.053

Neufeld, L., Rubio, M. & Gutiérrez, M. (2012). Nutrición en Colombia II. Actualización del estado nutricional con implicaciones en política. Nota técnica # 502. Bogotá D. C.: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. 50 pp.

Ocampo, J., Coppens d’Eeckenbrugge, G. & Jarvis, A. (2010). Distribution of the genus Passiflora L. Diversity in Colombia and its potential as an indicator for biodiversity management in the Coffee Growing Zone. Diversity, 2, 1158-1180.

https://doi.org/10.3390/d2111158

Ocampo, J. (2013). Diversidad y distribución de las Passifloraceae en el departamento del Huila en Colombia. Acta Biológica Colombiana, 18(3), 511-516.

Oliveira, V. B., Yamada, L. T., Fagg, C. W. & Brandão, M. (2012). Native foods from Brazilian biodiversity as a source of bioactive compounds. Food Research International, 48, 170-179.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2012.03.011

Omotayo, A. O. & Aremu, A. O. (2020). Underutilized African indigenous fruit trees and food–nutrition security: Opportunities, challenges, and prospects. Food and Energy Security, 9, 1-16.

https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.220

Osorio, C., Carriazo, J. G. & Almanza, O. (2011). Antioxidant activity of corozo (Bactris guineensis) fruit by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. European Food Research and Technology, 233(1), 103-108.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-011-1499-4

Pacheco, L. M. (2005). Nutritional and ecological aspects on buriti or aguaje (Mauritia flexuosa Linnaeus filius): A carotene-rich palm fruit from Latin America. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 44(5), 345-358.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03670240500253369

Patiño, V. M. (1989). Bibliografía etnobotánica parcial, comentada, de Colombia y los países vecinos. Bogotá D. C.: Instituto Colombiano de Cultura Hispánica. 371 pp.

Pérez-Gutiérrez, R. M., Muñiz-Ramírez, A., Gómez, Y., Bautista, E. (2010). Antihyperglycemic, antihyperlipidemic and antiglycation effects of Byrsonima crassifolia fruit and seed in normal and Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 65(4), 350-357.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-010-0181-5

Pinela, J., Carvalho, A. M., Ferreira, I. C. F. R. (2017). Wild edible plants: Nutritional and toxicological characteristics, retrieval strategies and importance for today's society. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 110, 165-188.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2017.10.020

Pulido, M. T., Pagaza-Calderón, E. M., Martínez-Ballesté, A., Maldonado-Almanza, B., Saynes, A. & Pacheco, R. M. (2008). Homegarden as an alternative for sustainability: Challenges and perspectives in Latin America. In Albuquerque, U. P. & Ramos, M. A. (Eds.). Current Topics in Ethnobotany. Pp. 55-79. Kerala, India: Research Signpost.

Rodríguez-Mora, D. F., Velásquez-Ávila, H. A., Fernández-Alonso, J. L. & Raz, L. (2019). Los usos tradicionales de las plantas no maderables de Santa María, Boyacá (Andes Colombianos). Serie de Guías de Campo del Instituto de Ciencias Naturales de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia No. 22. Bogotá D. C.: AES Colombia y Universidad Nacional de Colombia. 381 pp.

Romero-Castañeda, R. (1991). Frutas silvestres de Colombia. Segunda edición. Bogotá D. C.: Instituto Colombiano de Cultura Hispánica. 661 pp.

Sarmiento, E. (1986). Frutas en Colombia. Bogotá D. C.: Ediciones Cultural Colombiana Ltda. 155 pp.

Sharma, S. M., Sharma, S., Pattabhi, V., Mahato, S. B., & Sharma P. D. (2007). A Review of the hepatotoxic plant Lantana camara. Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 37(4), 313-352.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10408440601177863

Spina, M., Cuccioloni, M., Sparapani, L., Acciarri, S., Eleuteri, A. M., Fioretti, E. & Angeletti, M. (2008). Comparative evaluation of flavonoid content in assessing quality of wild and cultivated vegetables for human consumption. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 88, 294-304.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.3089

Toro, J. L. (2012). Árboles de las Montañas de Antioquia. Medellín: Corporación Autónoma Regional del Centro de Antioquia (CORANTIOQUIA). 203 pp.

Van den Eynden, V., Cueva, E. & Cabrera, O. (2003). Wild foods from Southern Ecuador. Economic Botany, 57(4), 576-603.

Van Zonneveld, M., Larranaga, N., Blonder, B., Coradin, L., Hormaza, J. I. & Hunter, D. (2018) Human diets drive range expansion of megafauna-dispersed fruit species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1-6.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1718045115

Villa, D. & García, N. (2017). Food plants in home gardens of the middle Magdalena basin of Colombia. Caldasia, 39(2), 292-309.

https://doi.org/10.15446/caldasia.v39n2.63661

Yamaguchi, K. K. L., Pereira, L. F. R., Lamarão, C. V., Lima, E. S. & Veiga-Junior, V. F. (2015). Amazon acai: Chemistry and biological activities: A review. Food Chemistry, 179, 137-151.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.01.055

Yuyama, K., Aguiar, J. & Yuyama, L. 2002. Camu-camu: um fruto fantástico como fonte de vitamina C. Acta Amazonica, 32(1),169-174.

https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-43922002321174

Supplementary material

Appendix 1. List of wild edible fruits of Colombia. *Endemic species. Management: w (wild), w/c (wild/cultivated). Use region: Ama (Amazon), And (Andes), Car (Caribbean), Cau (Cauca Valley), Mag (Magdalena Valley), Pac (Pacific), Ori (Orinoco), SNSM (Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta).

1Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Bogotã, Colombia.

* Autor para correspondencia.