Abstract (en):

Abstract (es):

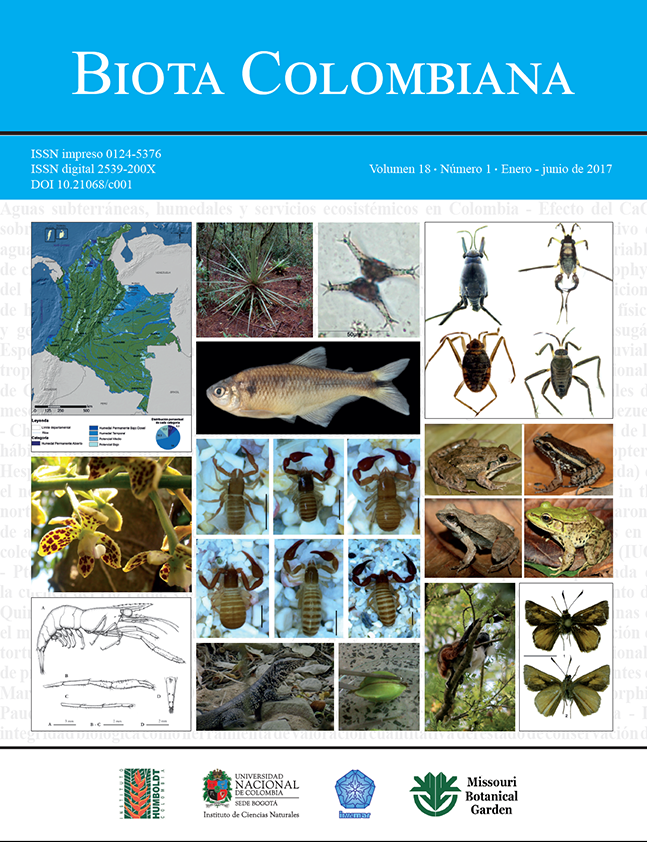

El Chocó biogeográfico (Colombia) es una región biodiversa pero afectada drásticamente por la minería. En

este trabajo, se identificaron las especies de plantas vasculares que colonizan áreas afectadas por minería en

bosques de la región; en concreto, se recolectaron plantas en diferentes formaciones topográficas de siete minas

abandonadas (3-15 años de abandono después del cese de la actividad minera) en tres municipios de la región.

Se identificaron 66 especies, 47 géneros y 22 familias. Las familias más representativas fueron Cyperaceae

(14,9 % géneros y 25,8 % especies), Melastomataceae (14,9 y 15,2 %) y Rubiaceae (10,6 y 12,1 %), mientras

que los géneros con más especies fueron Cyperus (8,5 % especies), Rhynchospora (8,5 %), Scleria (6,4 %) y

Spermacoce (6,4 %). La forma de vida predominante fue la herbácea (80,3 % especies) y los hábitats con más

especies fueron las llanuras no inundables (36,3 % especies), el ecotono (34,8 %) y las depresiones cenagosas

(31,8 %). Las depresiones cenagosas incluyeron más especies exclusivas (42,8 %, n = 42). La revegetación

temprana de las minas depende de la historia de vida de las plantas colonizadoras y de factores asociados al

sustrato.

Keywords:

Gold mining. Habitat preference. Herbaceous vegetation. Primary succession. Species richness (en)

References

Andrade-C, G. 2011. Estado del conocimiento de la biodiversidad en Colombia y sus amenazas. Consideraciones para fortalecer la interacción cienciapolítica. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 35: 491-507.

APG III. 2009. An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the order and families of flowering plants: APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161: 105-121.

Ash, H. J., R. P. Gemmell y A. D. Bradshaw. 1994. The introduction of native plant species on industrial waste heaps: a test of immigration and other factors affecting primary succession. Journal of Applied Ecology 31: 74-84.

Asprilla, A., C. Mosquera, H. Valoyes, H. Cuesta y F. García. 2003. Composición florística de un bosque pluvial tropical (bp-T) en la parcela permanente de investigación en biodiversidad (PPIB) en Salero, Unión Panamericana, Chocó. Pp: 39-44. En: García, F., Y. Ramos, J. Palacios, J. Arroyo, A. Mena y M. González (Eds.). Salero, Diversidad biológica de un bosque pluvial tropical (bp-T). Guadalupe Ltda, Bogotá, Colombia.

Ayala, J. H., J. Mosquera y W. I. Murillo. 2008. Evaluación de la adaptabilidad de la acacia (Acacia mangium Wild), y bija (Bixa orellana L.?) en áreas degradadas por la actividad minera aluvial en el Chocó biogeográfico, Condoto, Chocó, Colombia. Bioetnia 5: 115-123.

Bernal, R., S. R. Gradstein y M. Celis. 2015. Catálogo de plantas y líquenes de Colombia. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. http://catalogoplantasdecolombia.unal.edu.co.

Bradshaw, A. D. 1992. The biology of land restoration. Pp: 25-44. En: Jain, S. K. y L. W. Botsford (Eds.). Applied population biology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Netherlands.

Bradshaw, A. D. 1997. Restoration of mined land–using natural processes. Ecological Engineering 8: 255-269.

Capitán, L. F. 1994. Platina española para Europa en el siglo XVIII. Llull 17: 289-312.

Chase, M. W. y J. L. Reveal. 2009. A phylogenetic classification of the land plant to accompany APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161: 122-127.

Díaz, W. A. y S. Elcoro, S. 2009. Plantas colonizadoras en áreas perturbadas por la minería en el estado Bolívar, Venezuela. Acta Botánica Venezuelica 32: 453-466.

Estrada-Villegas, S., J. Pérez-Torres y P. Stevenson. 2007. Dispersión de semillas por murciélagos en un borde de bosque montano. Ecotropicos 20:1-14

Forero, E. y A. Gentry. 1989. Lista anotadas de plantas del Chocó. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales. Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Guadalupe Ltda. Bogotá, Colombia. 142 pp.

Fuentes-Ramírez, A., A. Pauchard., L. A. Cavieres y R. A. García. 2011. Survival and growth of Acacia dealbata vs. native trees across an invasion front in south-center Chile. Forest Ecology and Management 261: 1003-1009.

Galeano, G. 2000. Forest use at the pacific coast of Chocó, Colombia: a quantitative approach. Economic Botany 54: 358-376.

Gentry, A. H. 1986. Species richness and floristic composition or Chocó region plant communities. Caldasia 15: 71-75.

Gentry, A. H. 1996. A field guide to the families and genera of woody plants of North West South America: (Colombia, Ecuador, Perú): with supplementary notes on herbaceous taxa. Conservation International, Washington DC. 895 pp.

Gobernación del Chocó. 2015. Nuestro departamento - Chocó, información general. Recuperado el 20 de junio, 2015 de: http://www.choco.gov.co/informacion_general.shtml.

Guevara, R., J. Rosales y E. Sanoja. 2005. Vegetación pionera sobre rocas, un potencial biológico para la revegetación de áreas degradadas por la minería de hierro. Interciencia 30: 644-652.

Haston, E., J. E. Richardson, P. F. Stevens, M. W. Chase y D. J. Harris. 2009. The linear angiosperm phylogeny group (LAPG) III: a linear sequence of the families in APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161: 128-131.

Hernández-Acosta, E., E. Mondragón–Romero, D. Cristóbal-Acevedo, J. E. Rubiños-Panta y E. Robledo-Santoyo. 2009. Vegetación, residuos de mina y elementos potencialmente tóxicos de un jal de Pachuca, Hidalgo, México. Revista Chapingo 15: 109-114.

Hoyos, J. F. 1990. Los árboles de Caracas. Monografía Nº 24. Sociedad de Ciencias Naturales La Salle, Caracas, Venezuela. 409 pp.

Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi - Igac. 2017. Mapas físico-políticos: departamento de Chocó. Recuperado de: http://geoportal.igac.gov.co/mapas.

Leal, C. 2009. La compañía minera Chocó Pacífico y el auge del platino en Colombia, 1897-1930. Historia crítica Ed. Especial: 150-164.

Mahecha, G. E. 1997. Fundamentos y metodología para la identificación de plantas. Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, Lerner Ltda, Bogotá, Colombia. 282 pp.

Poveda-M, C., C. A. Rojas-P., A. Rudas-LI y J. O. Rangel-Ch. 2004. El Chocó biogeográfico: ambiente físico. Pp: 1-22. En: Rangel-Ch., J. O. (Ed.). Colombia diversidad biótica IV, El Chocó biogeográfico/Costa Pacífica. Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Conservación Internacional, Bogotá, Colombia.

Ramírez-Moreno, G. y E. Ledezma-Rentería. 2007. Efecto de las actividades socioeconómicas (minería y explotación maderera) sobre los bosques del departamento del Chocó. Revista Institucional Universidad Tecnológica del Chocó 26: 58-65.

Rangel-Ch., J. O. 2004. Amenazas a la biota y a los ecosistemas del Chocó biogeográfico. Pp: 841-866. En: Rangel-Ch., J. O. (Ed.). Colombia diversidad biótica IV, El Chocó biogeográfico/Costa Pacífica. Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Conservación Internacional, Bogotá, Colombia.

Rangel-Ch., J. O. y O. Rivera-Díaz. 2004. Diversidad y riqueza de espermatofitos en el Chocó biogeográfico. Pp: 83-104. En: Rangel-Ch., J. O. (Ed.). Colombia diversidad biótica IV, El Chocó biogeográfico/Costa Pacífica. Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Conservación Internacional, Bogotá, Colombia.

Rangel-Ch., J. O., O. Rivera-Díaz, D. Giraldo-Cañas, C. Parra-O., J. C. Murillo-A., I. Gil y C. Berg. 2004. Catálogo de espermatofitos en el Chocó biogeográfico. Pp: 105-439. En: Rangel-Ch., J. O. (Ed.). Colombia diversidad biótica IV, El Chocó biogeográfico/Costa Pacífica. Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Conservación Internacional, Bogotá, Colombia.

Rodrigues, R. R., S. Venâncio, y L. C. de Barro. 2004. Tropical Rain Forest regeneration in an area degraded by mining in Mato Grosso State, Brazil. Forest Ecology and Management 190: 323–333.

Simberloff, D. y B. Von Holle. 1999. Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: inversional meltdown? Biological Invasions 1: 21-32.

Valois-Cuesta, H. 2016. Sucesión primaria y ecología de la revegetación de selvas degradadas por minería en el Chocó, Colombia: bases para su restauración ecológica. Tesis de doctorado. Universidad de Valladolid. España, Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenierías Agrarias, Instituto Universitario de Investigación en Gestión Forestal Sostenible. Palencia, España, 199 pp.

Valois-Cuesta, H., C. Martínez-Ruiz, Y. Y. Rentería y S. M. Panesso. 2013. Diversidad, patrones de uso y conservación de palmas (Arecaceae) en bosques pluviales del Chocó, Colombia. Revista de Biología Tropical 61: 1869-1889.

Walker, L. R. y R. Del Moral. 2003. Primary succession and ecosystem rehabilitation. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 456 pp.

How to Cite

The works published in the journals of the Alexander von Humboldt Biological Resources Research Institute are subject to the following terms, in relation to copyright:

1. The patrimonial rights of the published works are assigned to Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt. The authors or institutions that elaborate the document agree to transfer the patrimonial rights to the Humboldt Institute with the sending of their articles, which allows, among other things, the reproduction, public communication, dissemination and dissemination of works.

2. The works of digital editions are published under a Creative Commons Colombia license:

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional.

> Attribution - Non-commercial - No Derivative: This license is the most restrictive of the six main licenses, it only allows others to download the works and share them with others, as long as their authorship is acknowledged, but they cannot be changed in any way, nor can they be used commercially.

3. The authors, when submitting articles to the editorial process of the magazines published by the Humboldt Institute, accept the institutional dispositions on copyright and open access.

4. All items received will be subjected to anti-plagiarism software. The submission of an article to the magazines of the Humboldt Institute is understood as the acceptance of the review to detect possible plagiarism.

5. The works submitted to the editing process of the magazines of the Humboldt Institute must be unpublished.