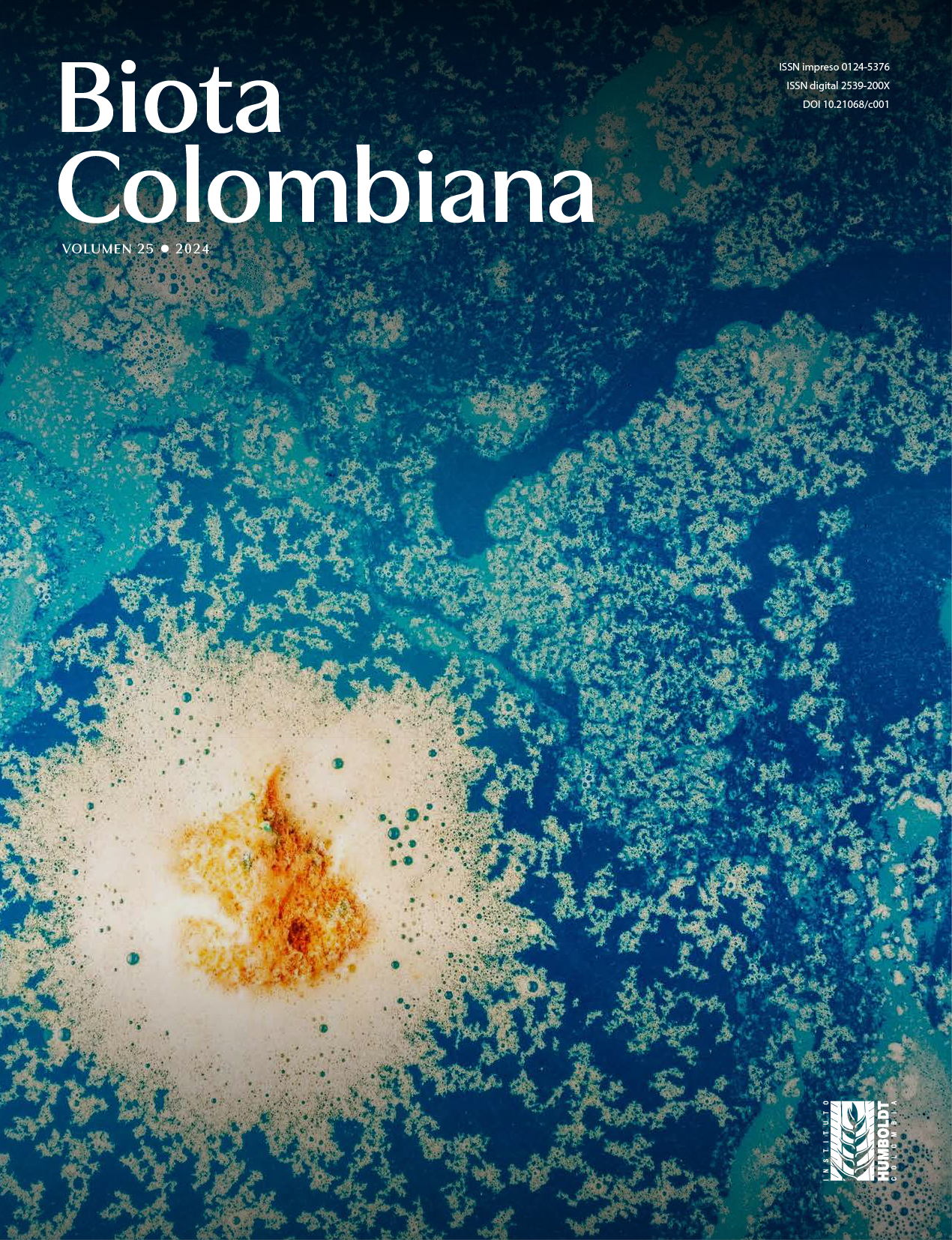

Recibido: 24 de agosto de 2023; Aceptado: 22 de marzo de 2024; : 27 de mayo de 2024

Resumen

La prevención y mitigación de los conflictos con el hombre son prioritarias para la conservación de los grandes carnívoros. La caza por venganza tras la depredación del ganado es una de las principales amenazas para el jaguar (Panthera onca) y el puma (Puma concolor) en América. Se consultaron registros de informes gubernamentales, agencias de recursos naturales, medios de comunicación y observaciones de campo para caracterizar el conflicto entre humanos y grandes felinos en el Parque Nacional Natural Paramillo de Colombia. Entre 2007 y 2022, se reportaron 37 eventos de depredación de grandes felinos sobre perros domésticos y ganado, de los cuales el 84 % correspondió a ataques de jaguares. Se encontró que los animales más depredados, en orden de ataques, fueron cerdos, perros, ovejas y vacas. Los excesos de matanza (es decir, > 1 animal atacado en un evento de depredación) representaron el 61 % de todos los eventos de depredación. Los principales obstáculos para el manejo son la insuficiencia de personal para verificar la depredación y la falta de protocolos operativos claros. Finalmente, se identifican estrategias para reducir el riesgo de depredación y mejorar la gestión actual.

Palabras clave:

conflicto humano-vida silvestre, Panthera, área protegida, Paramillo, comunidades rurales.Abstract

Prevention and mitigation of conflict with humans are priorities for large carnivore conservation. Retaliatory hunting following livestock depredation is one of the main threats to jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor) in the Americas. Records from government reports, natural resource agencies, media, and fieldwork observations were consulted to characterize human-big cat conflict in Colombia’s Paramillo National Natural Park. From 2007 to 2022, big cat depredation on domestic dogs and livestock was characterized by 37 events, 84 % of which corresponded to attacks by jaguars. The most predated animals, in order of attacks, were pigs, dogs, sheep, and cows. Surplus killings (i.e. > 1 animal attacked in a depredation event) accounted for 61 % of all depredation events. The main management barriers are insufficient personnel to verify depredation and a lack of clear operational protocols. Finally, strategies to lower depredation risk and improve current management are identified.

Keywords:

human-wildlife conflict, Panthera, protected area, Paramillo, rural communities..Introduction

Human-carnivore coexistence is constrained by competition for space and resources, particularly in heavily modified ecosystems (Carter & Linnell, 2016). In recent decades, this coexistence has been increasingly replaced by conflict, as habitat loss accelerates and inadequately managed livestock supplants populations of natural prey (Hoogesteijn & Hoogesteijn, 2011). Expanding cattle pastures and poor livestock management practices increase the risk of human-big cat conflict (Michalski et al., 2006), a concept that refers to interactions between humans and wild felids with negative consequences for both (Castaño-Uribe et al., 2016; Zimmermann et al., 2021).

Livestock depredation by jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor) has caused unfavorable perceptions towards these carnivores in rural Latin America, particularly among cattle ranchers (Castaño-Uribe et al., 2016; Figel et al., 2016). Considering that one of the main causes of jaguar and puma population decline is the conflict stemmed from attacks on domestic animals (Michalski et al., 2006; Azevedo & Murray, 2007; Salcedo-Rivera et al., 2022), it is necessary to consider a cultural perspective and the concerns of relevant stakeholders.

The socioecological dynamics of rural Colombia (related to violence, land grabbing, extensive cattle ranching and agricultural practices) and a limited State presence have produced a continuous flow of human populations towards forests and conservation areas, triggering negative interactions with big cats (Castaño-Uribe et al., 2016). The area around Paramillo National Natural Park (hereafter Paramillo) is historically recognized for its complex social dynamics, as it has experienced a constant population turnover caused by decades of persistent armed conflict (Salas-Salazar, 2016).

Paramillo is an area of considerable socioecological importance partly due to its diversity of ecosystems and status as the ninth largest protected area in Colombia’s Natural Parks system. Spanning 4600 km², Paramillo contains multiple ecosystems, including the largest extension of tropical forest in northern Colombia (Corporación Autonoma Regional de los Valles del Sinú y San Jorge, 2020). With 101 species, the Alto Sinú and San Jorge subregions have the richest mammalian species diversity in Colombia (Chacón et al., 2022), and are habitat to six felid species: jaguar (P. onca), puma (P. concolor), ocelot (Leopardus pardalis), oncilla (Leopardus tigrinus), margay (Leopardus wiedii), and jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi) (Racero-Casarrubia et al., 2015).

In Colombia there are significant information gaps regarding human-big cat conflict. Knowledge is especially lacking in areas previously affected by social unrest and violence, which have difficulted scientific fieldwork. This is the case of Paramillo, a historical stronghold of armed guerilla groups (Garcia-Corrales et al., 2019). The objective of this research is to characterize human-big cat conflict in Paramillo through a comprehensive analysis of records of domestic animals attacked by jaguars and pumas from 2007-2022. Since buffer zones are often hotspots for human-carnivore conflict (Dhungana et al., 2019), a better understanding of attack frequencies in relation to proximity to the protected area boundary was targeted. Management recommendations to reduce depredation risk and prevent retaliatory killings of big cats in the region are also provided.

Methods

Study area

The study area focuses on Paramillo National Natural Park and its surrounding buffer zone, located in the department of Córdoba in northwestern Colombia. The department has an expansive network of waterways composed mainly of the Sinú and San Jorge rivers. Paramillo has an extension of 4600 km² with an elevational gradient ranging 200-3960 m. Average annual rainfall is 3500-4 000 mm, and average annual temperature ranges from 26-30 °C (IDEAM, 2013).

The study area includes local communities, Afro-descendant and indigenous Embera Katío communities located within Paramillo and its buffer zone. In the department of Córdoba, jaguars and pumas are widely recognized by local communities and represented in local cultures and customs (Racero-Casarrubia et al., 2008; Figel et al., 2022).

Human communities practice traditional agriculture in addition to domestic animal husbandry (chickens, pigs, and sheep). Management reports and direct observations indicate significant increases in livestock ranching in and around Paramillo. As a result, Paramillo has one of the highest deforestation rates among protected areas in the country (Clerici et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the park remains one of the most important habitats in northern Colombia for connecting jaguar and puma populations of regions such as Darién, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Serranía del Perijá and Serranía de San Lucas (Castaño-Uribe et al. 2013).

Data collection

To identify big cat depredation events in Paramillo, management and field reports produced by Paramillo official staff (PNNPAR) (n = 4) and the Regional Autonomous Corporation of the Sinú and San Jorge valleys (n = 16) (Corporación Autonoma Regional de los Valles del Sinú y San Jorge, 2020) between January 2007 and April 2022 were reviewed. Location and date of depredation incidents, attacking species, species attacked, number and estimated age of the animals attacked, and type of production management were then recorded. In addition, depredation events verified in the field during our surveys of the Ayapel-Paramillo jaguar corridor were included. The identification of depredation events was conducted following the general protocol of Hoogesteijn & Hoogesteijn (2011). Finally, a web search on press releases and local news stories reporting on depredation events was carried out, with the following keywords: “attacks,” “conflict,” “depredation,” “jaguar”, “Paramillo”, and “puma”.

Data analysis

A study area map was created using ArcGIS Pro (v. 10.8.1, ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA, USA), obtaining the national park and indigenous territory shapefiles from Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia (2017) and the Colombian Agencia Nacional de Tierras (2020).

The survey focused on surplus killings because these events can rapidly exacerbate negative perceptions and prompt a disproportionate number of retaliatory actions by local communities towards large carnivores (Lucherini et al., 2018). Thus, Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare frequencies of surplus killings by location (inside buffer zones vs. within National Park boundaries) and season (rainy vs. dry). All statistical analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2020).

To estimate the financial impacts caused by jaguar and puma depredation, the average body weight of each type of domestic animal and its average market value in Colombian pesos were used. This value was converted to USD and multiplied by the number of domestic animals lost.

Results

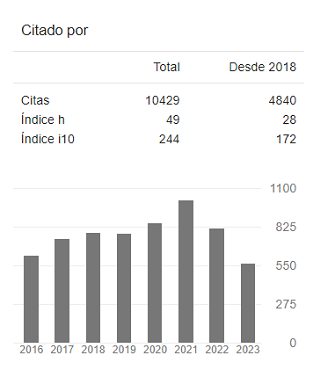

A total of 37 depredation events were recorded, corresponding to the loss of 92 domestic animals. Between 2007 and 2022, 32 attacks by jaguars and 4 attacks by pumas were reported. Domestic pigs were most frequently attacked (n = 16 events), followed by dogs (n = 9), sheep (n = 6) and cattle (n = 6) (Figure 1). The average number of fatalities per attack was 2.44 ± 1.86 SD, with the highest rates for sheep and dogs (Table 1). Both jaguars and pumas were responsible for surplus killings (i.e. > 1 domestic animal attacked in a depredation event), with mortality rates, in the case of dogs, as high as 10 individuals/attack. Average numbers of animals lost per attack were 3.5 ± 1.64 for sheep, 3.14 ± 3.53 SD for dogs, 2.08 ± 1 SD for pigs, and 1.67 ± 0.52 SD for cows. Only one of the ten cows lost was an adult; the rest were calves. Big cat depredation resulted in economic losses of approximately $15 647 ($1043 per year).

Figure 1: Loss of domestic animals from jaguar and puma attacks in and around Paramillo National Natural Park, Colombia, between 2007-2022.

Across all years, the most conflict-prone areas were clustered in the northern and northeastern section of Paramillo (Figure 2). The buffer zone was the setting of 21 of the attacks, while 14 attacks occurred inside the boundaries of the national park. A disproportionate number of attacks on dogs occurred inside the park, where 33 % of these events occurred. Overall, however, there was no significant correlation between the occurrence of surplus killings inside vs. outside the park (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.45).

Human-big cat conflict affected 29 distinct settlements in Paramillo and its surrounding buffer zone (x̄ = 1.23 ± 0.68 SD incidents per settlement experiencing conflict). Jaguars and pumas attacked livestock in 24 and 2 settlements, respectively; 3 settlements experienced repeat attacks by jaguars; and 1 settlement experienced attacks by both big cats. In three cases, the attacking big cat could not be confirmed due to lack of verifiable evidence or untimely reporting by local communities. Depredation events occurred at an average elevation of 236 m.a.s.l. ± 223 m (range 77-1125 m.a.s.l.) and 20 (54 %) of the attacks occurred within 5 km of a river. While livestock attacks were recorded every month, there was some seasonal variation in these events; 47 % of all attacks occurred between July and October, which corresponds to a period that receives 40 % of annual precipitation. But there was no significant correlation between the occurrence of surplus killings by season (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.23).

Discussion

Despite widespread occurrence of pumas and jaguars throughout the study area (Chacón et al., 2022), records of puma attacks were found at only two sites. By comparison, reports of jaguar attacks were more numerous and widespread. Nonetheless, the number of depredated animals documented is lower than those recorded in other studies. For example, in a similarly sized study area of Mexico, Amador-Alcala et al. (2013) documented the loss of 270 domestic animals from jaguar depredation over a three-year period, and in a 150 km² study area in the Brazilian Pantanal, jaguars and pumas killed 32 bovines over two years (Azevedo & Murray, 2007).

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of depredation events (n = 37) on domestic animals by big cats in relation to geographic variables in and around Paramillo National Park, Colombia, 2007-2022.

Animal

# of attacks (total # of indiv. lost)

% of surplus attacks

Avg. number of indiv. lost per attack (SD)

Avg. elevation of attacks (SD)

Avg. distance of attacks from park boundary (SD)

Avg. distance of attacks from nearest river (SD)

Pig

16 (34)

62.5

2.08 (1.00)

275.27 (205.47)

5.91 (5.07)

6.18 (5.90)

Dog

9 (22)

42.9

3.14 (3.53)

393 (362.32)

8.14 (6.31)

6.87 (7.00)

Sheep

6 (26)

83.3

3.5 (1.64)

118.33 (34.26)

3.90 (2.91)

4.63 (2.01)

Cow

6 (10)

66.7

1.67 (0.52)

156.17 (54.41)

4.53 (5.52)

4.4 (2.99)

Figure 2: The geographic location of the study area and spatial distribution of depredation between 2007-2022 in Paramillo National Natural Park, Colombia.

Before making cross-country comparisons, it is worth noting that depredation events are inconsistently reported in Paramillo and that these results should therefore be considered minimum estimates. Rather than filing formal complaints with local management agencies, cattle ranchers and local hunters often choose to kill big cats clandestinely. The lack of effective human-big cat conflict response is particularly notable in the mountainous southern portion of the park, which has historically been a major stronghold of armed groups and therefore off-limits to biological research (Salas-Salazar, 2016). Due to its rugged terrain, southern Paramillo also has low levels of livestock ranching compared to the northern areas.

Despite the relatively low numbers of depredation cases documented, the loss of even a few pigs, sheep, or cows causes significant economic impacts on local and indigenous communities. Regarding the attacks on dogs, these events were commonly associated with hunters, since the animals killed were bloodhound dogs used by people to hunt species such as paca (Cuniculus paca), armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus and Cabassous centralis), and peccaries (Pecari tajacu and Tayassu pecari).

Descriptive information on depredation events reveals that attacks were associated with instances of opportunistic attacks by big cats on domestic animals, largely supported by inadequate husbandry and livestock management practices (Hoogesteijn et al., 2002; Thirgood et al., 2005; Hoogesteijn & Hoogesteijn, 2008). The most common management deficiencies identified were the lack of supervision and monitoring of livestock, the proximity of pastures to felid habitats (Rabinowitz, 2005; Kolowski & Holekamp, 2006), and the usage of inadequate pens or paddocks to house livestock at night (Hoogesteijn et al., 2002; Wang & Macdonald, 2006; Hoogesteijn & Hoogesteijn, 2011; Corrales-Gutiérrez et al., 2016).

Dogs, in particular, follow local and indigenous communities in their activities, including hunting (Koster, 2009), and generate considerable impacts on ecosystems and native fauna through predation, resource competition, hybridization, and disease transmission to other animals and humans (Silva-Rodríguez & Sieving, 2012). Management actions are recommended to protect dogs, such as locking them in cages at night (Carral-García et al., 2021).

The persistent human-big cat conflict in and around Paramillo reveals that each situation has unique characteristics (Marchini et al., 2021; IUCN, 2020), and can be resolved by implementing conflict reduction and management strategies to protect domestic animals (Hoogesteijn & Hoogesteijn, 2011; Castaño-Uribe et al., 2016). Currently, low-cost solutions of less than the value of an average head of cattle ($500) can decrease depredation losses in hotspots of conflict. This includes the creation of nocturnal enclosures with wood, and the use of bells and collars with lights (Corrales-Gutiérrez et al., 2016). However, specially designed electric fences (5-6 wires) are one of the most effective and least costly tools to deter predators and decrease attacks on cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, and poultry (Scognamillo et al., 2002; Schiaffino et al., 2002; Polisar et al., 2003; Torres & Vineyard, 2003; Corrales-Gutiérrez et al., 2016; Ubiali et al., 2018; Khorozyan & Waltert, 2019; Nanni et al., 2020; Lodeiro-Ocampo et al., 2021; Ruffener, 2023). Ranchers should also implement modified grazing practices and management such as housing newborn calves in maternity paddocks to reduce depredation risk (Hoogesteijn & Hoogesteijn, 2011). The application of control measures and antipredatory strategies can improve livestock production, supporting changes in the perception towards felids and sustainable management of productive systems, thus allowing the tolerance of areas of coexistence and conservation of big cats (Quigley et al., 2015). This is why alternatives and solutions for the inclusion and participation of producers in the conservation plans of these species is fundamental to mitigate the negative impacts on the populations of large carnivores and on local livelihoods (Hoogesteijn & Chapman, 1997; García-Anleu et al., 2016).

A disconnect between local people reporting losses of domestic animals and management authorities responsible for addressing the issue was also identified. By regulation, wildlife management in the buffer zone is overseen by the Corporación Autonoma Regional de los Valles del Sinú y San Jorge (CVS) (Canal-Albán & Rodríguez, 2008). However, in Paramillo, the presiding agency is the Colombian National Parks Service (Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia). Lack of coordination between the agencies and insufficient government resources inhibit timely management measures aimed at preventing conflict. More trained staff is needed to deal with depredation events, which, in turn, would enable accurate decision making to make recommendations and implementations according to the needs of each ranch. Interactions between local and indigenous communities and CVS and PNNPARR must be based on collaboration to promote management that avoids retaliatory killings. Recommended steps to follow once a conflict case is reported are detailed in Figure 3.

Figure 3. : Proposal for a verification protocol to manage cases of human-big cat conflict in Paramillo National Natural Park, Colombia

Further research that elucidates the extent to which depredation is associated with the alteration of forests and hunting-induced decreases in the natural prey of these big cats is needed. The next step is to integrate this study’s results into an environmental education campaign so local people can gain awareness about the biocultural importance of big cats in Paramillo and learn evidence-based strategies to avoid conflict.

In conclusion, there is a constant threat to the conservation of large felines in the southern region of Córdoba. This phenomenon requires comprehensive attention from entities responsible for the conservation of natural resources and local communities coexisting with the predation of domestic animals. It is imperative to develop action plans to mitigate this phenomenon and protect the species involved.