Recibido: 11 de diciembre de 2023; Aceptado: 2 de septiembre de 2024; : 20 de enero de 2025

Resumen

Este trabajo documenta por primera vez la depredación del cangrejo de río Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) (Decapoda: Cambaridae) por Notonecta melaena Kirkaldy, 1897 (Insecta: Notonectidae). Estas dos especies coexisten en la reserva Club Náutico El Muña en la cordillera oriental de la región Andina colombiana. El potencial depredador de N. melaena sobre estadios juveniles de P. clarkii fue probado en cautiverio. Individuos de N. melaena fueron aislados en recipientes plásticos usando agua potable. La longitud corporal fue medida para depredadores y presas, y se registró el tiempo empleado en cada evento de depredación. Diez individuos de N. melaena depredaron sobre 150 individuos juveniles de P. clarkii. Las presas fueron consumidas en un rango de tiempo de entre 29 y 182 min (108,64 ± 45,74). Esta información sirve como base para futuros estudios centrados en determinar preferencias alimenticias y tasas de depredación por N. melaena, y el diseño de estrategias de control biológico de P. clarkii en ecosistemas andinos.

Palabras clave: insecto, especies invasoras, depredador, presa, biodiversidad dulceacuícola.Abstract

This work documents the predation of the crayfish Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) (Decapoda: Cambaridae) by the backswimmer Notonecta melaena Kirkaldy, 1897 (Insecta: Notonectidae) for the first time. The two species were observed coexisting at the Club Náutico El Muña reserve in the eastern range of the Colombian Andean region. The predatory potential of N. melaena on juvenile P. clarkii was tested under captivity conditions. Individuals of N. melaena were isolated in plastic containers using drinking water. Body lengths of predator and prey specimens were measured, and the time spent on each predation event was registered. Ten individuals of N. melaena preyed upon 150 individuals of P. clarkii. Prey consumption ranged from 29 to 182 min (108.64±45.74). This information serves as the foundation for future studies aimed at determining prey preferences and predation rates in N. melaena, which can be used in biological control strategies against P. clarkii in Andean ecosystems.

Palabras clave: insects, invasive species, predator, prey, freshwater biodiversity.Introduction

After habitat destruction, invasion of exotic species is the second most important factor associated with species extinction worldwide (Everett, 2000). Intentional or accidental species translocation leads to the establishment of invasive species and causes negative effects on native biodiversity because: 1) populations of introduced alien species can increase uncontrollably due to the lack of predators and parasites; 2) introduced alien species can be voracious predators, causing reductions or even disappearance of native species populations; and 3) introduced alien species could carry microscopic organisms, including pathogens and lethal parasites, that are harmful to native species (Kolar & Lodge, 2001). For these reasons, invasive alien species represent a significant threat to biodiversity and the functioning of aquatic ecosystems (Lodge et al., 2000).

One of the most well-known invasive freshwater alien species is the red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) (Decapoda: Cambaridae), a species native to northeastern Mexico and southern USA, introduced to all continents (except Antarctica and Oceania) and considered the most cosmopolitan freshwater crayfish species globally (Oficialdegui et al., 2020). P. clarkii is a generalist omnivore species that feeds on plant and animal detritus, macrophytes, mollusks, annelids, nematodes, flatworms, tadpoles, juvenile fish, and insects (Gutiérrez et al., 1998; Parkyn et al., 2001; Correia, 2002; Buck et al., 2003; Cruz & Rebelo, 2005). Its natural predators include fishes, birds, and some mammals (González et al., 2022). Small juvenile crayfish are especially vulnerable to potential insect predators such as odonates, coleopterans and hemipterans (Ulikowski et al., 2018).

P. clarkii shows an alternated cyclic dimorphism of sexually active and inactive periods during its lifecycle. After hatching, young individuals experience metamorphosis, followed by at least two weeks of voracious eating. Egg production is completed within six weeks, incubation and maternal attachment occurs within three weeks, and maturation can occur in eight weeks or more (Huner & Barr, 1991). Amer et al. (2015) showed that P. clarkii has 13 post-embryonic stages distinctly characterized by morphological and color changes, associated with increases in their total length at each stage. A summary of the information provided by Amer et al. (2015) is shown in Table 1.

P. clarkii negatively impacts habitats (Savini et al., 2010). Investigations report intensive predation, herbivory, pathogen transmission, alterations in habitat functions, competition, community dominance, and food web alteration (Souty et al., 2016), as well as modifications to ecosystem dynamics, socioeconomic damage to rice fields and disturbances to macrophyte communities by consumption and fragmentation (Twardochleb et al., 2013; Carreira et al., 2014). P. clarkii populations can become overabundant, predating intensely and decreasing the abundance and diversity of aquatic plants and animals in freshwater habitats (Maezono & Miyashita, 2004). This species can also degrade riverbanks, causing erosion and increasing water turbidity with its burrowing activity (Souty et al., 2014), as has been reported in the Cauca River and Colombian crop areas (Flórez & Espinosa, 2011).

Notes. Source: Amer et al. (2015).

Table 1: Summary of characteristics for post-embryonic stages of Procambarus clarkii.

Post-embryonic stages

Duration (days)

Total length (average in mm)

1

≤ 1

2.32

2

1

3.48

3

5

6.5

4

7

8.76

5

7

10.28

6

14

11.2

7

10

12.8

8

11

14.63

9

12

15.32

10

14

18.02

11

15

20.4

12

15

21

13

15

25.33

P. clarkii was introduced in Colombia in 1985 as an experimental species for commercial purposes in Valle del Cauca (Gutiérrez et al., 2012). In 1988 it was accidentally dispersed to other localities, drained by the Cauca River (Flórez & Espinosa, 2011). First records in the Bogotá savannah date as early as 2004, specifically in an artificial lake between Bogotá and the municipality of Briceño. The actual distribution of P. clarkii in Colombia includes several localities in Boyacá, Cundinamarca and Valle del Cauca (Gutiérrez et al., 2012; Pachón & Valderrama, 2018; Arias & Pedroza, 2018). According to Camacho et al. (2021), areas for this species in Colombia (predicted by niche modeling) are located in various ecosystems, such as tropical forests, basal forests, riparian forests and savannahs in the departments of Magdalena, Cesar, Córdoba, Atlántico, Arauca, Casanare, Meta and Vichada.

Heteropterans (Insecta: Hemiptera) of the infraorder Nepomorpha are diverse in aquatic ecosystems of the eastern Colombian Andes, including backswimmers of the genera Notonecta Linnaeus, 1758 and Buenoa Kirkaldy, 1904 (Padilla-Gil, 2019) (Nepomorpha: Notonectidae). Some species of these genera consume large amounts of mosquitos (Hoyos et al., 2014), other insects and their larvae, small crustaceans, copepods, annelids, mollusks, fish larvae, and frog tadpoles (Ahlgren et al., 2011; Diéguez & Gilbert, 2003; Florencio et al., 2012). The predator-prey relationship between these insects and small stages of decapods has also been recorded in ponds where shrimps are reared for commercial purposes in the Colombian Pacific (Padilla, 2014).

Notonecta are voracious predators, rapidly locating and capturing their prey using their sight and water vibrations (Papáček, 2013). Attacks by Notonecta individuals have shown negative effects on the growth and morphology of juvenile crayfish species such as Pacifastacus leniusculus (Dana, 1852) and Orconectes virilis (Hagen, 1870) (Dye & Jones, 1975; Hirvonen, 1992). Furthermore, negative effects on the survival of the crayfish Astacus leptodactylus (Eschscholtz, 1823), due to predation by Notonecta have been documented (Ulikowski et al., 2018).

Notonecta melaena Kirkaldy, 1897 has been reported from Mexico, El Salvador, and highland ecosystems in the eastern range of the Colombian Andean region (Hungerford, 1933; Davis, 1964; Padilla, 1994). Its life cycle lasts between 100 and 120 days (egg, five nymphal instars and the adult stage), and it is very abundant in aquatic habitats of the eastern Colombian Andean waters, where it predates on small crustaceans, mosquito larvae, snails, and amphipods (Padilla, 1994).

Despite both being common species, little is known about their trophic relationship. P. clarkii juveniles and N. melaena nymphs and adults occupy similar amphibiotic habits and microhabitats, making predator-prey encounters highly possible, yet difficult to observe. During this research, individuals of N. melaena and small immatures of P. clarkii were observed near the water’s edge of the Tominé dam at the Club Náutico El Muña reserve, which led to a preliminary hypothesis about the potential predation of N. melaena on P. clarkii juveniles. This report aims to contribute to fill the knowledge gaps regarding the natural enemies of P. clarkii in natural environments of the tropical Andean region by describing the predation of N. melaena in its juvenile stages.

Materials and methods

Aquatic fauna surveys were conducted between May and June 2023 in the Club Náutico El Muña reserve in the Tominé dam, Sesquilé municipality, Cundinamarca department, within the eastern mountain range of Colombia (05°00’ 24.2” N, 73° 48’ 30.2” W, 2600 m). The locality revealed a low species richness (10 spp.), but high abundances of the red swamp crayfish P. clarkii and the backswimmer N. melaena. This section of the Tominé dam is influenced by the sub-Andean forest and a variety of introduced plants (Palacino-Rodríguez et al., 2023), and it is possible that P. clarkii is currently having a negative impact on the aquatic diversity. N. melaena and P. clarkii coexist in submerged grass at depths of less than 20 cm, near the water’s edge.

Individuals of N. melaena and P. clarkii were collected using an aquatic insect net and deposited in 2 L plastic boxes containing water from the locality. Individuals were then transported to a laboratory. Each N. melaena individual was isolated in 200 mL plastic containers containing drinking water, 21±1 °C, L12:D12 photoperiod, and ca. 300 lux. Each container was labeled with a unique number. P. clarkii individuals were identified using characters of the first pleopod, chelae and cephalic process (Eversole, 2004). N. melaena individuals were sexed observing the gonapophysis in females and the genital capsule in males (Padilla, 1994). Body length of predator and prey specimens was measured with a micrometer attached to a 20X zoom binocular microscope. Time spent on each predation event was also registered. During five days, five males and five females of N. melaena were fed on fifteen occasions with one juvenile P. clarkii individual each. To provide a continuous food supply, individual preys were provided continuously. When a predator finished one prey, another prey was immediately provided, and the water was changed.

Results

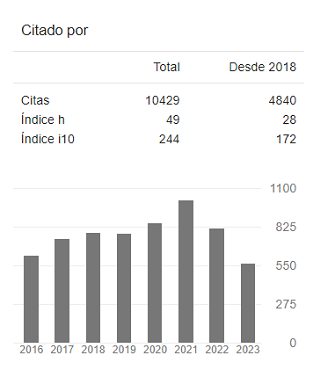

N. melaena individuals ranging in size from 9.62 to 11.63 mm (10.59±0.73) preyed on 150 P. clarkii individuals ranging in size from 7.9 to 17 mm (11.92±2.86) (Figure 1). Prey consumption lasted 29 to 182 min (108.64±45.74). After the preys were killed, they were released and sank to the bottom of the container. After several minutes (5-15 min) N. melaena individuals swam to the bottom of the container to grab the dead prey (or parts of it) and continued its consumption. Subsequently, the prey was released. These activities continued until the prey was fully consumed. All prey items supplied to N. melaena were consumed.

Figure 1: Predation on the swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii by the backswimmer Notonecta melaena in laboratory conditions.

Discussion

P. clarkii was first recorded from high Andean ecosystems in 2004 (Campos, 2005). However, research about its impact on biodiversity, behavior, and potential native enemies is currently inexistent. Only a single event of the mammal Didelphis pernigra J. A. Allen, 1900 predating P. clarkii in the eastern Andes has been reported (González et al., 2022). Therefore, this marks the first recorded instance of an aquatic insect preying on P. clarkii in the Andean region.

However, for species like P. clarkii, rapid population growth, parental care and resource competitiveness intensify their impact as consumers, exerting significant pressure on the cosystems they invade (Gherardi & Acquistapace, 2007). To counteract these effects, strategies such as population restoration of natural predators (like fish) and intensive trapping have proven to be effective in reducing the size of invasive crayfish populations (e.g., Hein et al., 2006; Aquiloni et al., 2010). Native predators could help control the abundance of introduced prey without causing negative effects on trophic cascades. In natural environments, juvenile crayfish begin to feed independently after their second juvenile stage, with the end of maternal care (Kozák et al., 2015). During this period, the potential pressure from predators such as Notonecta is thought to be limited. However, under captive conditions, juvenile crayfish lacking the protection of their mothers in a small area and at shallower depths made possible for Notonecta to search and trap juvenile crayfish at the bottom (Kozák et al., 2015). In fact, insect predators have been employed in biological control because their shorter life cycles result in fluctuations in population density in response to changes in the population sizes of their prey (Pijnakker et al., 2020).

Since populations are not homogeneous, most species undergo size variations during their ontogeny, resulting in the coexistence of different size classes within prey and predator populations (Rudolf, 2008). This is the case for both N. melaena (predator) and P. clarkii (prey). N. melaena are predators advantageous to their environments due to their ability to feed on a variety of prey and switch types of prey as one becomes more abundant, generating a sigmoid functional response that starts slowly and then increases rapidly until slowing again at high prey numbers (Weseloh & Hare, 2009). Although the predation rate in this specific predator-prey interaction is unknown, data show that fifth instar nymphs and adults of N. melaena consume at least three P. clarkii individuals between stages 4 and 12 each day.

Given that prey density and predation rates depend on prey handling time and attack rate (Byström & García, 1999), a reduced density for stages 4-12 (and possibly latter stages) of P. clarkii in this locality is expected due to high predation rates by N. melaena. Consequently, population densities for other species in this habitat could be less affected due to predation by P. clarkii. A recent study showed that removing young stages of the habitat may be essential for achieving effective control of invasive populations of P. clarkii (García-de-Lomas et al., 2020). These and other topics related to the trophic cascade will be focused on future research.

In conclusion, N. melaena is a voracious predator on several P. clarkii stages, consuming several preys per day. Although our data derives from experimental study in the laboratory, the proximity of these species in natural conditions, sharing the same microhabitats, suggests increased opportunities of encounters between prey and predator. This information will serve as the foundation for future studies, enabling us to understand prey preferences and predation rates of N. melaena.